Reliable biomarkers of high risk would open up the prospect of preventing Parkinson’s Disease during what looks to be a prolonged prodromal phase. Hyposmia, REM sleep behaviour disorder, synuclein-related neurodegeneration, and a novel MRI marker -- loss of dorsolateral nigral hyperintensity -- are all attracting interest.

People with idiopathic rapid eye movement behaviour disorder (RBD) seem to be at high risk of developing Parkinson’s Disease (PD) and so represent a promising group for biomarker research. We know, for example, that olfactory dysfunction at baseline in people with RBD predicts transition over two-three years to Lewy body disease.

In one of the most widely discussed developments, Werner Poewe and colleagues at the Medical University of Innsbruck, Austria, now seem to have detected a new MRI marker of prodromal Parkinson’s Disease in this high-risk population.

Follow the swallow tail

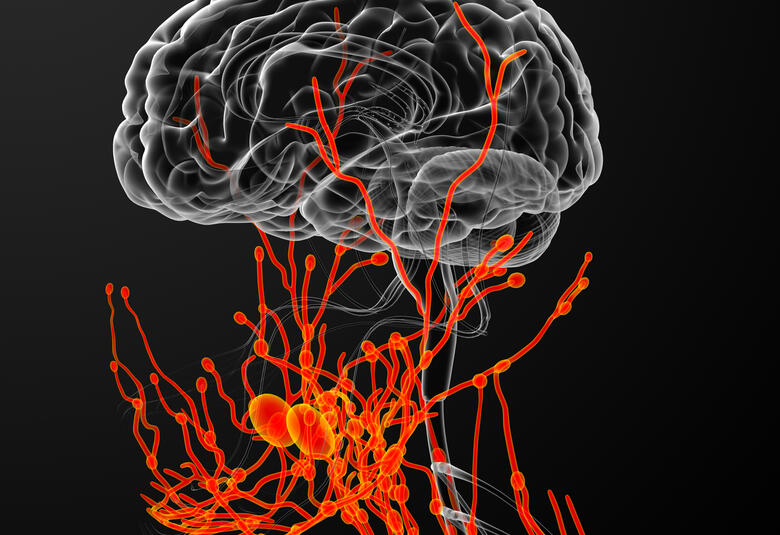

Among people with RBD studied by Professor Poewe and colleagues, two-thirds showed loss of dorsolateral nigral hyperintensity (DNH) on high-field susceptibility-weighted magnetic resonance imaging. Loss of this feature – known as the “swallow tail sign” -- was not seen in healthy controls; but it is lost in patients with clinical PD.

A case control study from the University of Nottingham, UK, had suggested previously that absence of the swallow-tail sign is 90% accurate in diagnosing PD. Its disappearance may relate to reduced neuromelanin content in the substantia nigra.

But multimodality imaging will probably be required to fully characterize early PD pathology and monitor its progression. Philippe Remy, Université Paris-Est, Créteil, France, described ways of measuring loss of dopaminergic cells that may be helpful to neuroprotective strategies.

Insights from nuclear medicine

While structural imaging (DNH excepted) seems to have little to offer in early diagnosis, both PET and SPECT hold promise. Use of ligands of the dopamine transporter enables SPECT to chart decreasing uptake in the substantia nigra with increasingly severe disease; and PET using the fluorine-18 DOPA tracer to measure binding to DA terminals shows progressive neuronal loss from early to late stages of disease.

Early intervention requires biomarkers that identify people at high risk.

Alpha-synuclein toxicity

Aggregation of alpha-synuclein seems to be involved in several neurodegenerative conditions, including PD, and is the main component of Lewy bodies. From animal models, it looks increasingly likely that cell-to-cell transmission of misfolded alpha-synuclein is the mechanism underlying disease progression, and that oligomeric alpha-synuclein is the toxic species. If so, targeting it could be neuroprotective, and its selective removal might lead to restoration of function.

We do not yet have a way of measuring alpha-synuclein in the brain. But oligomeric alpha-synuclein levels in CSF and exosomal alpha-synuclein in plasma are promising biomarkers in the diagnosis of PD, Wassilios Meissner, Institute of Neurodegenerative Diseases, University of Bordeaux, France, told the meeting.

Since alpha-synuclein pathology is not confined to the brain, efforts are being made to see if its presence in accessible tissues – notably the skin – can be used as a marker of early PD.

Oligomeric alpha-synuclein levels may distinguish PD patients from healthy controls

The broader biomarker picture

Cognitive decline in PD is associated with increased levels of amyloid and tau proteins in CSF. So these Alzheimer-associated markers may be helpful. Ongoing research is also seeking to find systemic markers of the inflammatory processes believed to be at least partly responsible for idiopathic PD and its atypical variants such as multiple system atrophy and progressive supranuclear palsy.

Even when patients are assessed by clinicians experienced in movement disorders, around 15% of those diagnosed with PD do not in fact have the idiopathic disease. At least as many patients who have PD on autopsy have not been diagnosed with the condition. And as many as 30% of patients with a diagnosis of PD on presentation subsequently have their diagnosis revised. This is the extent of diagnostic uncertainty based on physical examination and clinical history alone.

Biomarkers in people at high risk would help greatly with diagnosis, and assessment of progression and response to therapy. They might also allow us to identify patients at risk of developing PD long before classical symptoms appear. Biomarkers would certainly enable enrichment of trial populations, so reducing the number of people enrolled; and their causal links to clinical progression may eventually be sufficiently well established for them to act as surrogate endpoints.

Our correspondent’s highlights from the symposium are meant as a fair representation of the scientific content presented. The views and opinions expressed on this page do not necessarily reflect those of Lundbeck.